Rare earth prices have turned and increased rapidly.

- Share

- From

- mining.com

- publisher

- William Chang

- Issue Time

- Aug 18,2017

Summary

Amid stiff competition for title of commodity with biggest booms and biggest busts (nickel anyone?), rare earths take top honours.

Participants in the rare earth industry have been through the grinder over the past decade.

Amid stiff competition for title of commodity with biggest booms and biggest busts (nickel anyone?), rare earths take top honours.

Here's a quick recap of what brought us here:

- 80 years ago placer deposits in India and Brazil, and later monazite ore from South Africa meet the world's REE demand, such as there was.

- The US steps in but after five decades as the world's top source Molycorp mothballs Mountain Pass in 2002.

- China quickly establishes a monopoly on global production and then panics markets by introducing export quotas in 2005.

- REE prices goes into the stratosphere (for example, dysprosium prices do a bitcoin, rocketing from $118/kg to $2,262/kg between 2008 and 2011).

- Scores of explorers jump into the space with Canadians and Australians finding deposits all over the world from Manitoba to Malawi.

- Old mine plans are dusted off and punters pour billions into the sector.

- Trade spats ensue, lobby groups spring up and politicians even find ways to bash Barack Obama over rare earths.

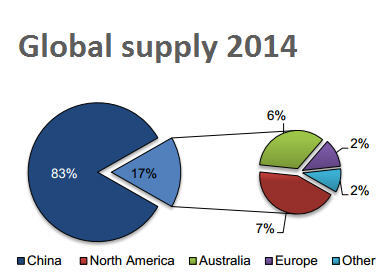

Source: Roskill

- Rare earths become the basis for a bestselling video game and Hollywood comes to the party, albeit late, using samarium as a plot device and confusing entertainment writers everywhere.

- REE prices begin to tank even before production outside China ramps up and stock in bellwethers Molycorp and Australia's Lynas dive.

- The WTO finally rules on the legality of China's export restrictions – years after the quotas became irrelevant.

- When Kim Jong-Un gets in on it, it's a sign the industry has hit rock bottom.

Now it seems a turnaround may be in the offing.

And again you have China to thank.

Faced with growing discontent at home, China's new leadership in March declared a war on pollution.

And its low-tech and dirty REE industry is firmly in the crosshairs.

Beijing has been cracking down on the industry for years. But smuggling, environmental devastation and dangerous artisinal mining practices remain rampant.

Some estimates put exports from illegal mining through networks in Vietnam and Hong Kong as highs as 40,000 tonnes, matching China's annual quotas, further depressing prices.

Beijing is poised to impose a bunch of new environmental regulations including green export certificates and new taxes that are based on the value of the minerals, rather than on volume as is the case at present.

Rare earth production taxes are pegged at RMB60 ($9.14) per tonne mined for light rare earth operations and RMB30 for medium and heavy rare earth operations.

Any increase will mean higher prices at the producer level, particularly for rare earths with greater value such as europium, terbium and neodymium, and a reduction in stockpiles. At least that's the intention.

Official English outlet China Daily reports the move aims to reflect the scarcity of the minerals (China maintains it only has 23% of the world's REE reserves even though it still produces more than 80% of the global total) and the impact of extraction.

Businessweek quotes Chen Huan, a rare earth analyst with Beijing Antaike Information Development, a research unit of the state-backed China Nonferrous Metals Industry Association, as saying the new rules could see prices rise more than 20% from current levels.

Higher prices are not just useful for Beijing in terms of better environmental regulation, but as most of the larger miners and processors are state-owned, higher prices affect the bottom line directly

While prices rose and fell more or less in unison, predictions are that prices of the 17 elements may begin diverging more – particularly between lights and heavies. It's an outlier, but praseodymium prices are already up 60% from a year ago and at times trade for as much as $140 per kilogram oxide.

While not quite as sanguine as other market observers, research house and rare earth authority Metal-Pages also sees signs of a turnaround in REE prices which could occur "across the board in 2015" as supply and demand factors become more balanced.

The London and Beijing-based data provider in its latest outlook cites a number of factors for optimism about prices and the viability of new mining projects outside China:

- Smuggling has subsided slightly, due to low prices and China's ongoing crackdown

- Prices have become uneconomic for many producers

- Recycling of REEs remain difficult and expensive and the impact on supply and therefore prices could be a decade away

- Demand for high-powered magnets could grow 5%–8% over the next decade

- Forced consolidation and vertical integration of Chinese industry should reduce competition and make output control easier

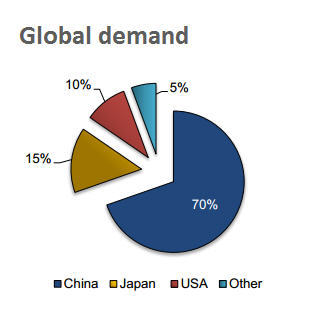

- Chinese domestic consumption already at 70% of global total, is expected to rise sharply as it ramps up domestic clean energy and moves into more high-tech sectors

- After WTO ruling against it Beijing's strategy is shifting from export to production control

- The Baotou Rare Earth Products Exchange launched in March should encourage private sector stockpiling a la Fanya Metal Exchange

The lifting of export quotas as mandated by the WTO (China is appealing the ruling, but doesn't really have a better chance to make its case stick a second time around) is not expected to have an influence on prices.

Exports since 2005 has not even come close to the export ceiling and over the past three years, quotas were more than 20,000 tonnes above actual exports.

What could have an impact is the removal of export taxes on rare earths products which have been raised and widened on several occasions and are now levied at 15% – 20% by the country's General Administration of Customs.

Roskill Information Services says in a new report scrapping these taxes could affect non-Chinese producers by potentially reducing FOB rare earth prices, and bring it in line with domestic Chinese prices.

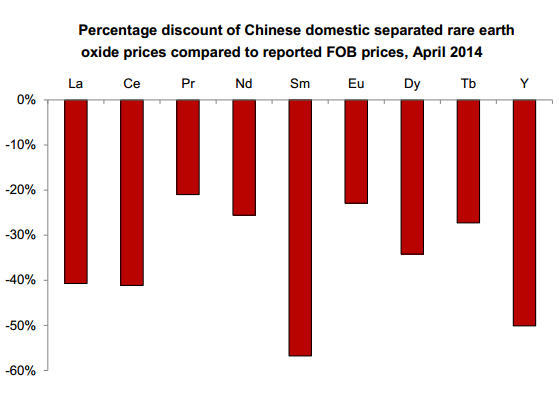

The impact, at least in the short term, could be significant as domestic prices were on average 36% below reported FOB prices in April this year according to David Merriman, senior analyst at the London-based metals and minerals consultancy.

However, says Merriman, both FOB and Chinese domestic prices are expected to increase based on new tighter control of production and increasing costs.

Source: Roskill

Another reason why there is room for new producers is the increasing prevalence of captive supply.

Purchasers of raw material that produce downstream rare earths products like powders and magnetic alloys are eligible for a 16% VAT rebate.

That's one of the reasons Chinese producers like Inner Mongolia Baotou Steel Rare Earth Group and Chinalco have invested heavily in downstream facilities (thanks to its three Chinese plants, Molycorp also happens to be one of the companies benefiting from the rebate).

"Increased captive supply since 2012 has resulted in a greater portion of rare earth raw materials and intermediate products not being made available even to the Chinese domestic market and thus reducing supply for other consumers," says Merriman.

The biggest longer term threat to the industry is substitution.

Rocketing prices in 2010–2011 sent consumers scurrying to find alternatives and ways to use less with tolerable results.

Metal-Pages says depending on the industry and companies involved consumption fell between 25% – 75%: "One of the most dramatic cases is the reduction in the use of dysprosium in high performance NdFeB magnets. Magnet makers have successfully reduced use by 50-75% and for some magnets or eliminated it all together."

While much higher prices would be a more than welcome development for the dozens of rare earth explorers and developers that are still out there, another panic in the West on pricing would only lead to long-term demand destruction.

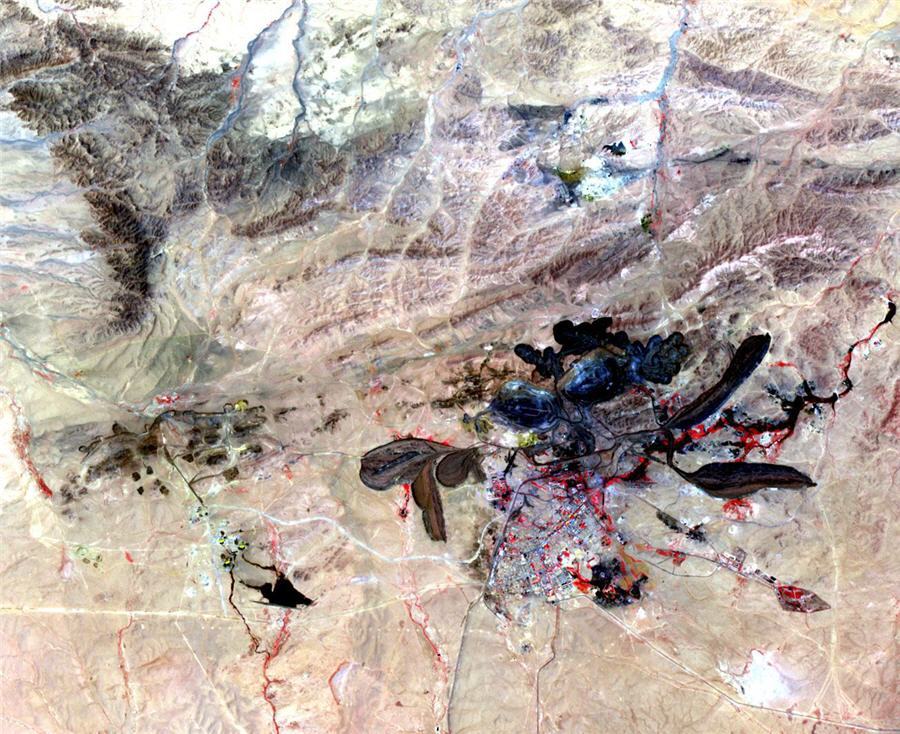

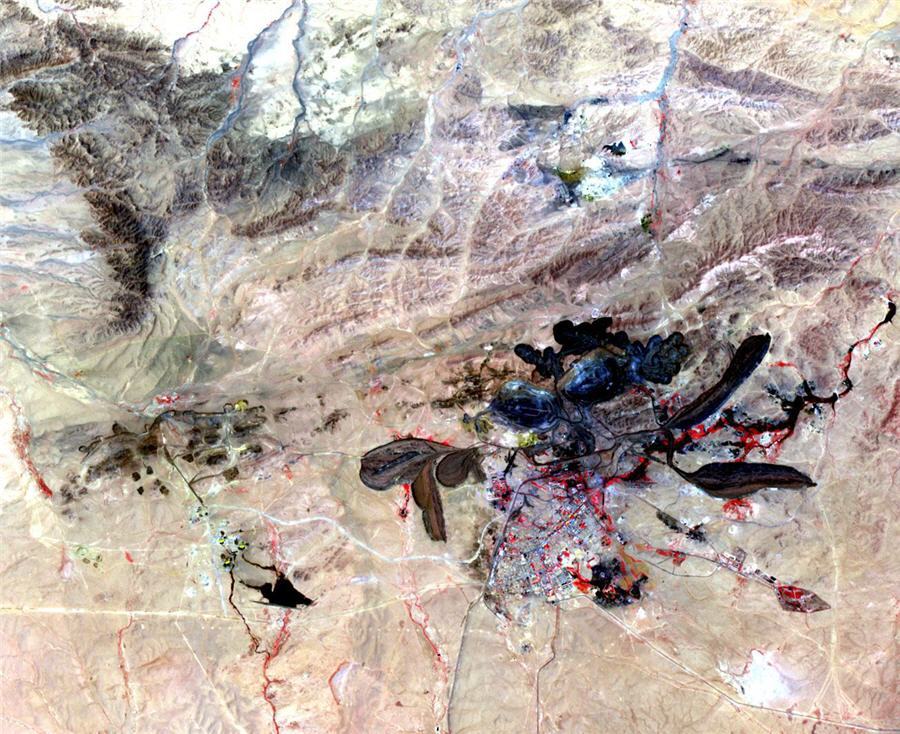

The giant mine in Bayan Obo, Inner Mongolia near Baotou City, produces almost a third of the world's rare earths and does so as a byproduct of iron ore mining.